2023 problem log

WARNING: spoilers ahead!

- day 1

- day 2

- day 3

- day 4

- day 5

- day 6

- day 7

- day 8

- day 9

- day 10

- day 11

- day 12

- day 13

- day 14

- day 15

- day 16

- day 17

- day 18

- day 19

- day 20

Day 1

Tougher than a usual day 1! The second part in particular requires you to either find overlapping matches (1twone -> [1, two, one]) or to search from the end to the front.

I solved it by detecting overlapping matches with a neat regular expression trick: a lookahead capture group. The key idea is that if you put a capture group inside a lookahead group (denoted by (?= )), you'll get a match but won't consume any of the string; this allows you to find overlapping matches.

>>> import re

>>> re.findall("(?=(\d|two|one))", "1twone")

['1', 'two', 'one']

Day 2

A nice easy start-of-season problem today. First I solved it the straightforward way, by parsing the file into a dictionary of lists, then iterating through each game in the dictionary.

Afterwards, I realized that all you need is the maximum red, green and blue values from each line; so I wrote a little function to pull out one color's maximum with a regular expression:

def maxi(line, color):

return max(int(x) for x in re.findall(rf"(\d+) {color}", line))

And then the solutions basically just fall out as two generator expressions:

print(

sum(

i + 1

for i, line in enumerate(open("input.txt"))

if maxi(line, "red") <= 12

and maxi(line, "green") <= 13

and maxi(line, "blue") <= 14

)

)

print(

sum(

maxi(line, "red") * maxi(line, "blue") * maxi(line, "green")

for line in open("input.txt")

)

)

Day 3

A tricky one for an early Sunday! I feel like I made a meal out of it, but AoC feels like that about 75% of the time anyway.

For part one, I got stuck for a while on a program that solved the sample problem but not the full problem. Finally, I added debugging output and the problem became immediately apparent:

I was counting newline characters as symbols! Everything worked once I stripped the newlines, but I waited way too long to add proper debug output.

Lesson 1: quality debugging output is worth its weight in gold

Lesson 2: have a low threshold for spending a minute adding debug input

Once I had completed it in a pretty messy way, I thought of a much neater solution.

For part 2, I made a start at solving it the same way I did part 1: checking each number, then checking if it was connected to a *, then checking if was connected to another number.

I almost got it working, but it was super fiddly, when I realized that if I started from the * instead of from the numbers, everything would be much simpler. And it was!

Day 4

Python sets to the rescue.

The set operators that python added are amazingly helpful when solving AoC problems, and they made short work of today's relatively easy problem. The meat of part 1, after turning the two "hands" into sets, relies on the & intersection operator:

def score(a, b):

intersection = a & b

return 2 ** (len(intersection) - 1) if intersection else 0

print(sum(score(*parse(line)) for line in sys.stdin))

Part 2 I solved as a triply-nested loop; I'm sure there's some easy closed-form solution, but thankfully the problem space was small and we didn't need to find it today:

bonus = defaultdict(int)

for i, line in enumerate(sys.stdin):

winners, mine = parse(line)

n = len(winners & mine)

bonus[i] += 1

for j in range(bonus[i]):

for k in range(i + 1, i + n + 1):

bonus[k] += 1

print(sum(bonus.values()))

Later, I noticed that a loop can be removed because we're just adding 1 bonus[i] times:

for i, line in enumerate(sys.stdin):

winners, mine = parse(line)

n = len(winners & mine)

bonus[i] += 1

for k in range(i + 1, i + n + 1):

bonus[k] += bonus[i]

which makes it about 15x faster.

Day 5

Part 1 was pretty easy; after parsing the file into lists of ranges and adjustments, go through each adjust each seed if it matches a range:

def run(seed: int, intervals: list[list[tuple[tuple[int, int], int]]]) -> int:

for map in intervals:

for (a, b), adj in map:

if a <= seed <= b:

seed += adj

break

return seed

seeds, intervals = parse()

print(min(run(s, intervals) for s in seeds))

For part 2, I had an answer that worked in theory but wouldn't finish before the heat death of the universe on the actual puzzle input.

I'm pretty sure that the answer has to do with merging all the ranges into a single list of ranges, but I didn't figure out exactly how to do it.

It's hard for me to write down that I failed on it!

Day 6

Who needs functions? Today's answer as a pair of one-liners:

in1, in2 = itertools.tee(sys.stdin)

# part 1

print(

prod(

sum(1 for p in range(t) if (t - p) * p > d)

for t, d in zip(*[[int(x) for x in re.findall(r"\d+", line)] for line in in1])

)

)

# part 2

print(

prod(

sum(1 for p in range(t) if (t - p) * p > d)

for t, d in [[int("".join(re.findall(r"\d+", line))) for line in in2]]

)

)

The only challenge today was converting the problem description into a function:

$$distance = (time limit - press) * press$$

My answer could be a lot more efficient; for one the function is symmetric about the middle so if we started in the middle, we could search outwards in one direction and stop iterating once we found a value that was too low, cutting the search space by roughly 75%.

I also could have actually solved for the intersection of d and the distance function above, but why do more thinking when the computer can just chug? My friend Chris shows the way if you prefer to think instead of type.

However, the function that stupidly searches the whole space only takes a couple seconds to run on my machine so I just had some fun converting it into single generator expressions.

Also, today I learned about math.prod! I'd written my own version so many times but today I decided to check if one existed and lo and behold, it does.

Day 7

I got my first couple of guesses wrong today because I have coded poker hand scoring before, and I scored the poker hands like real poker rather than "desert poker".

Instead of ranking them by the order of the cards in the hand (32222 > 2AAAA because 3 > 2), I initially ranked them like you would in real poker, where 2AAAA beats 32222 because four aces beats four twos.

With the simplified scoring, my answer was boring and straightforward:

def parse(iter):

hands = []

faces = {"T": 10, "J": 11, "Q": 12, "K": 13, "A": 14}

for line in iter:

hand, bid = line.strip().split(" ")

hand = [int(faces.get(c, c)) for c in hand]

hands.append((hand, int(bid)))

return hands

def score(hand):

hand, _ = hand

(_, n), *rest = sorted(

# turns a hand like [5,6,7,7,7] into [(5, 1), (6, 1), (7, 3)]

# then, we sort it by count and value so that we have the cards

# in order of frequency and then rank

Counter(hand).items(), key=lambda x: (x[1], x[0]), reverse=True

)

if n == 5:

return (7, *hand)

(_, nn) = rest.pop(0)

if n == 4:

return (6, *hand)

if n == 3 and nn == 2:

return (5, *hand)

if n == 3:

return (4, *hand)

if n == 2 and nn == 2:

return (3, *hand)

if n == 2:

return (2, *hand)

return (1, *hand)

I have only ever used collections.Counter for advent of code, but boy is it handy for AoC.

With a scoring function written, all that's left is to parse the hands and sum the winnings:

hands = parse(sys.stdin)

print(sum((i + 1) * bid for i, (_, bid) in enumerate(sorted(hands, key=score))))

To solve part 2, I changed the value of a jack from 11 to 1, and only had to make minor alterations to the score function:

def score(hand):

hand, _ = hand

js = hand.count(1)

(top, n), *rest = sorted(

Counter(hand).items(), key=lambda x: (x[1], x[0]), reverse=True

)

if top == 1:

n = rest.pop(0)[1] if rest else 0

if n + js == 5:

return (7, *hand)

nn = rest.pop(0)[1] if rest else 0

if n + js == 4:

return (6, *hand)

if n + nn + js == 5:

return (5, *hand)

if n + js == 3:

return (4, *hand)

if n + nn + js == 4:

return (3, *hand)

if n + js == 2:

return (2, *hand)

return (1, *hand)

Thanks to my friend Chris who pointed out that all we care about for ranking hands is the cardinality of ranks (i.e. the number of each rank in the hand), leading to this terrible golfed generator expression for part 1 that eliminates the score and parse functions entirely:

print(

sum(

(i + 1) * bid

for i, (_, bid) in enumerate(

sorted(

[

(

[

int({"T": 10, "J": 11, "Q": 12, "K": 13, "A": 14}.get(c, c))

for c in cards

],

int(bid),

)

for cards, bid in [line.split(" ") for line in sys.stdin]

],

key=lambda hb: list(sorted(Counter(hb[0]).values(), reverse=True))

+ hb[0],

)

)

)

)

Day 8

A day where a tiny bit of thinking saves you from wasting your computer's processing power. If you try to run part 2 until it finishes, you're likely to be waiting a long while.

First, parse the network into a dictionary:

def parse(iter):

directions = [1 if c == "R" else 0 for c in list(next(iter).strip())]

next(iter)

network = {}

for line in iter:

a, l, r = re.findall(r"\w+", line)

network[a] = (l, r)

return (directions, network)

Next, you need a function for finding the length of a cycle (from an A node to a Z node):

def cycle_len(directions, network, loc):

for i, dir in enumerate(itertools.cycle(directions)):

loc = network[loc][dir]

if loc[-1] == "Z":

return i + 1

for part 1, find the cycle length for AAA:

directions, network = parse(sys.stdin)

print(cycle_len(directions, network, "AAA"))

for part 2, find the least common multiple (using numpy.lcm) of the cycle length of all nodes ending with A:

print(

np.lcm.reduce(

[cycle_len(directions, network, node) for node in network if node[-1] == "A"]

)

)

update: Today I learned that there is a math.lcm in the standard library, since version 3.9! I love removing dependencies.

print(

math.lcm(

*(cycle_len(directions, network, node) for node in network if node[-1] == "A")

)

)

Day 9

I thought this one was going to require me to figure out the math, but a simple iterative model was plenty fast enough.

For part 1, we want to find the sum of the numbers added to the sequence. First I take the differences and save the final number of each list:

ls = []

while any(a != b for a, b in itertools.pairwise(ints)):

ls.append(ints[-1])

ints = [b - a for a, b in itertools.pairwise(ints)]

Then I build back up the sum and return it:

sum = ints[0]

for b in reversed(ls):

sum += b

return sum

At this point, I noticed that "sum" is equal to the additional number (ints[0]) and the last number of each row, simplifying that to:

return sum([ints[0]] + ls)

For part 2, the first half of the answer is the same, except I save the first number in each row instead of the last. Then build back up to the first value by taking the difference of the first number and the current value:

cur = ints[0]

for b in reversed(ls):

cur = b - cur

return cur

I'm sure there's a similar simplification of this process, but I'm feeling a little dense this morning and I'm leaving it where it is.

To parse the input and print the results, I have:

in1, in2 = itertools.tee(sys.stdin)

print(sum(part1([int(x) for x in line.split()]) for line in in1))

print(sum(part2([int(x) for x in line.split()]) for line in in2))

update: I realized that part 2 is the reverse of part 1! So you can remove the part2 function and express part 2 in terms of part 1 as:

in1, in2 = itertools.tee(sys.stdin)

print(sum(part1([int(x) for x in line.split()]) for line in in1))

print(sum(part1(list(reversed([int(x) for x in line.split()]))) for line in in2))

Day 10

Phew, that was a lot!

Parse the map into a grid:

I had a vague sense for part 2 that there was a parity-based solution, but I had to look at somebody else's answer for how to implement it.

I'm just going to post the link to my code, it's a bit of a mess and I don't feel like writing about it today.

Day 11

Parse the input into a set of points:

def parse(iter):

pts = set()

for row, line in enumerate(iter):

for col, c in enumerate(line.strip()):

if c != ".":

pts.add((row, col))

return pts

It turns out in part 2 that storing a grid would be catastrophic, so make sure you're just storing the location of the galaxies.

Find the rows and columns that lack galaxies, and thus need expanding:

pts = sorted(parse(sys.stdin))

rows = {p[0] for p in pts}

cols = {p[1] for p in pts}

ecols = set(range(max(cols))) - cols

erows = set(range(max(rows))) - rows

Then, expand them:

part1 = set()

part2 = set()

for row, col in pts:

part1.add(

(

row + len([i for i in erows if i < row]),

col + len([i for i in ecols if i < col]),

)

)

part2.add(

(

row + len([i for i in erows if i < row]) * 999_999,

col + len([i for i in ecols if i < col]) * 999_999,

)

)

We multiply by the expansion factor 1_000_000 - 1 because we already have the one row; it's not listed here but the expansion factor for the first part is 2 because we're doubling the empty rows.

Finally, sum the Manhattan distance between each pair of points. itertools.combinations is helpful here:

print(

sum(

abs(x1 - x2) + abs(y1 - y2)

for (x1, y1), (x2, y2) in itertools.combinations(part1, 2)

)

)

print(

sum(

abs(x1 - x2) + abs(y1 - y2)

for (x1, y1), (x2, y2) in itertools.combinations(part2, 2)

)

)

Day 12

Parsing the problem isn't the challenge:

def parse(iter):

lines = []

for line in iter:

cond, lens = line.strip().split(" ")

lines.append((cond, tuple(int(x) for x in lens.split(","))))

return lines

The challenge is implementing our own little regular expression engine! For part 1, this was enough, but for part 2 @functools.cache came to the rescue.

Why spend time thinking when we can memoize instead? Tables rule everything around me.

@functools.cache

def count(s: str, machines: tuple[int]) -> int:

if not machines:

if "#" not in s:

return 1

return 0

i = 0

l = len(s)

m = machines[0]

n = 0

while i < l + m and "#" not in s[:match]:

match = i

while i < l and s[i] in ["?", "#"] and i - match < m:

i += 1

if i - match == m and (i == l or s[i] in [".", "?"]):

n += count(s[i + 1 :], machines[1:])

i = match + 1

return n

Unfolding part 2 and outputting the sum, presented without comment:

def unfold(s: str, machines: tuple[int]) -> tuple[str, tuple[int]]:

return "?".join([s] * 5), machines * 5

puzzles = parse(sys.stdin)

# part 1

print(sum(count(s, machines) for (s, machines) in puzzles))

# part 2

print(sum(count(*unfold(*x)) for x in puzzles))

I wish I hadn't left it for the end of the day, when my brain is mashed potatoes, but glad I got it done!

Part 2 takes about .8 seconds with vanilla python, and .7 seconds with pypy.

Day 13

I decided to treat the input as a list of strings, and deal with vertical symmetries the same as horizontal symmetries by transposing the list.

The first thing I wrote was my transpose function, which uses the neat trick that zip(*grid) is a generator of rows for a transposed grid:

def t(g: list[str]) -> list[str]:

return list("".join(y) for y in zip(*g))

next up, a function to check if a grid is symmetric about a horizontal line:

def is_symmetric(g: list[str], i: int) -> bool:

l = len(g)

for j in range(1, min(i + 1, l - i - 1)):

if g[i - j] != g[i + j + 1]:

return False

return True

for part 1, it took me a while to read the part of the problem that said we need to sum all axes of symmetry. Eventually I got to this function to return the sum for a grid's horizontal symmetries:

def symmetry(g: list[str]) -> int:

return sum(

i + 1

for i, (a, b) in enumerate(itertools.pairwise(g))

if a == b and is_symmetric(g, i)

)

Then we can wrap part 1 up by summing the vertical symmetries (which I calculate as the horizontal symmetries of the transposed grid) and the horizontal symmetries * 100:

print(

sum(

symmetry(t(grid)) + 100 * symmetry(grid)

for grid in [

[line.strip() for line in chunk.split("\n")]

for chunk in sys.stdin.read().strip().split("\n\n")

]

)

)

for part 2, I started by writing a function that checks whether two lines are different by one character:

def onediff(a: str, b: str) -> bool:

return sum(a != b for a, b in zip(a, b)) == 1

Then a messy function that tries to unsmudge a grid's horizontal symmetry:

- if any pair of lines are equal or different by one

- search outwards for lines with one difference

- if setting those lines equal adds a symmetry, return that value

- search outwards for lines with one difference

def unsmudge(g: list[str]) -> int:

l = len(g)

for i, (a, b) in enumerate(itertools.pairwise(g)):

if a == b or onediff(a, b):

for j in range(min(i + 1, l - i - 1)):

if onediff(g[i - j], g[i + j + 1]):

h = g[:]

h[i - j] = g[i + j + 1]

if is_symmetric(h, i):

return i + 1

return 0

Finally, sum up the horizontal smudges * 100 and the vertical smudges:

print(

sum(

unsmudge(grid) * 100 or unsmudge(t(grid))

for grid in [

[line.strip() for line in chunk.split("\n")]

for chunk in sys.stdin.read().strip().split("\n\n")

]

)

)

Day 14

I decided to call the "immovable rocks" pins, by analogy to a pinball machine.

rocks, pins = [], []

maxrow = 0

for row, line in enumerate(sys.stdin):

rocks += [[n.start(), row] for n in re.finditer("O", line)]

pins += [[n.start(), row] for n in re.finditer("#", line)]

maxrow = row + 1

Tilting the board is finding the largest impediment in the same column, and putting the rock in the next row. It's important here that the rocks are already sorted by row, we need to move each row in turn to get the right answer.

for i, (col, row) in enumerate(rocks):

rocks[i][1] = (

max([r for c, r in rocks + pins if r < row and c == col] + [-1]) + 1

)

Then sum the row values of each rock to get the answer for part 1:

print(sum(maxrow - r for _, r in rocks))

For part 2, I first wrote a correct but slow implementation of running one cycle; I won't put it here because it's very similar to tilting the board north, but in each direction. You can read it here if you like.

I knew that my code would never finish, but also that the value of 1_000_000_000 was a hint that you weren't expected to run that many cycles, so I just ran my code and printed out each cycle's value in turn, figuring that there would be a loop.

I looked at the output in my text editor, picked a random value and found that it was at lines 134, 193, 252, so I guessed that there was a 59-element loop. Python told me that $$134 + 59 \times (\lfloor1,000,000,000 / 59\rfloor-2) = 999,999,984$$ , so the element 16 after line 134 should be the answer. I tried entering the value at line 150 as the answer, and it was correct!

I have implemented the cycle finding in code for past AoCs, but I haven't bothered to do it here so far. I kind of enjoy the simplicity of having figured it out by hand.

Day 15

for part 1, hash the whole string:

def hash(s: str) -> int:

sum = 0

for c in s:

sum = ((sum + ord(c)) * 17) % 256

return sum

instructions = sys.stdin.read().strip().split(",")

print("part 1:", sum(hash(i) for i in instructions))

for part 2, I used the fact that python dictionaries are ordered to my advantage. Each box is a dictionary, and inserting a lens goes to the back by default.

boxes = defaultdict(dict)

for i in instructions:

if "-" in i:

try:

del boxes[hash(i[:-1])][i[:-1]]

except KeyError:

pass

else:

label, val = i.split("=")

boxes[hash(label)][label] = int(val)

print(

"part 2:",

sum(

(box + 1) * (i + 1) * foc

for box in boxes

for i, foc in enumerate(boxes[box].values())

),

)

That's it! easy one today.

Day 16

I often make mistakes on problems like today's by getting types confused, so I started today with a few type aliases:

Grid = list[list[str]]

Point = tuple[int, int]

Dir = int

Beam = tuple[Point, Dir]

Cache = set[Beam]

Then set up some constants for directions, and transition tables for handling the mirrors and advancing in a given direction:

L, D, R, U = [1, 2, 3, 4]

mirror_a = {L: U, U: L, D: R, R: D} # \

mirror_b = {L: D, U: R, D: L, R: U} # /

advance = {

U: lambda pos: ((pos[0] - 1, pos[1]), U),

D: lambda pos: ((pos[0] + 1, pos[1]), D),

L: lambda pos: ((pos[0], pos[1] - 1), L),

R: lambda pos: ((pos[0], pos[1] + 1), R),

}

There's a small helper function for checking if a given Beam is valid:

def valid(beam: Beam, maxrow: int, maxcol: int) -> bool:

return 0 <= beam[0][0] < maxrow and 0 <= beam[0][1] < maxcol

I initially represented the beams as a list, but found that I ended up with lots of duplicates, so I changed it to be a set instead. The run function takes a set of beams, updates each of them, stores the points we've hit in a set, and returns the updated set of beams and set of points:

def run(

grid: Grid, beams: set[Beam], points: set[Point], cache: Cache

) -> tuple[set[Beam], set[Point]]:

newbeams = {b for beam in beams for b in update_beam(grid, beam, cache)}

for (row, col), _ in newbeams:

points.add((row, col))

return (newbeams, points)

The meat of the execution takes place inside update_beam, which I memoized for speed.

I particularly wanted to use the match statement today, it seemed like a good fit for the problem and I haven't tried it out very much.

An insight that greatly sped up my initial answer is that if we have seen a particular beam before, we don't need to run it at all any longer, because it can't hit any different spots than the beam that came before it. This allows me to return an empty set of beams if we've already run a particular beam, and reduced my part 2 runtime from 75 seconds to 4.

def update_beam(grid: Grid, beam: Beam, cache: Cache) -> set[Beam]:

if beam in cache:

return set()

(row, col), dir = beam

newdir = dir

pbeams = set() # possible new beams

maxrow = len(grid)

maxcol = len(grid[0])

match grid[row][col]:

case "|" if dir in [R, L]:

newdir = U

pbeams.add(advance[D](beam[0]))

case "-" if dir in [U, D]:

newdir = L

pbeams.add(advance[R](beam[0]))

case "\\":

newdir = mirror_a[dir]

case "/":

newdir = mirror_b[dir]

pbeams.add(advance[newdir](beam[0]))

pbeams = set(b for b in pbeams if valid(b, maxrow, maxcol))

cache.add(beam)

return pbeams

Now that it can execute a grid and beam set, I needed a function to run it until new cells stop getting hit. run_to_completion uses the heuristic that if the last 5 executions yielded the same result, it will assume execution is complete:

def run_to_completion(grid, beams={((0, 0), R)}):

cache = set()

points = {pos for pos, _ in beams}

n = 0

lastn = [-1, -1, -1, -1, -1]

while beams and n < 800:

beams, points = run(grid, beams, points, cache)

if all(n == len(points) for n in lastn):

break

lastn.append(len(points))

lastn = lastn[-5:]

n += 1

return points

It returns the set of points that have been visited, since that's all the information necessary for finding the answer.

To answer part 1, parse the input into a grid and run to completion from ((0,0), R), then print the number of points the program visited:

grid = [list(line.strip()) for line in sys.stdin]

print("part 1:", len(run_to_completion(grid)))

To answer part 2, make a list of all the possible starting beams, run each to completion, and find the largest:

maxrow = len(grid)

maxcol = len(grid[0])

print(

"part 2:",

max(

len(run_to_completion(grid, {((row, col), dir)}))

for (row, col), dir in [((row, 0), R) for row in range(maxrow)]

+ [((row, maxcol - 1), L) for row in range(maxrow)]

+ [((0, col), D) for col in range(maxcol)]

+ [((maxrow - 1, col), U) for col in range(maxcol)]

),

)

This runs in about 4 seconds on my laptop. It could be faster, but that will do for today I think.

Day 17

not completed yet

Day 18

For part 1, I wanted to use a cute trick I'd seen in past AoC puzzles to add tuples: store them as complex numbers.

What I wanted was that (0, 1) + (4,5) == (4, 6), but unfortunately that doesn't work with python tuples. However, if you encode (0,0) as the complex number 1j, and (4,5) as 4 + 5j, then 0j + 4+5j == 4+5j.

Conveniently, we can also multiply direction vectors times a length in this scheme. If I use the real part of the number to encode the x dimension and the imaginary part the y, then 1j represents an increase of 1 in the y dimension, and 8 * 1j is an increase of 8 in the y dimension.

After I parse the directions normally:

moves = []

for line in sys.stdin:

dir, dist, color = line.strip().split(" ")

moves.append((dir, int(dist), color.strip("()#")))

There are four directions to encode:

dirs = {"R": 1j, "L": -1j, "U": -1 + 0j, "D": 1 + 0j}

Then, for every move, add the depth and each point in the perimeter to our list of boundary points:

depth = 0

for dir, dist, _ in moves:

cur = points[-1]

depth += dist

for i in range(1, dist + 1):

points.append(cur + dirs[dir] * i)

Next I needed to find out how many squares are inside the perimeter, so I turned to my old friend the flood fill:

def floodfill(start, points: set[complex]):

stack = [start]

while stack:

pt = stack.pop()

for d in [1j, -1j, 1 + 0j, -1 + 0j]:

if pt + d not in points:

points.add(pt + d)

stack.append(pt + d)

Finally, sum up the depth of the perimeter and the number of squares inside it to give the part 1 answer. (I guessed that (1, 1) would be inside the perimeter for both the sample and my input, and was fortunately correct)

points = set(points)

l1 = len(points)

floodfill(1 + 1j, points)

l2 = len(points)

print("part 1:", depth + (l2 - l1))

For part 2, I figured that my flood fill would never finish, so I needed to calculate the perimeter analytically. To do so, I turned to Shapely, which has a polygon class that will calculate the area for you efficiently.

I changed the dirs table just a bit to handle the different parsing for part 2, but it was still mostly the same. This time I subtract one from the depth because we'll be calculating the area of the polygon including the perimeter, so we only want the additional holes:

# R L U D

dirs = {"0": 1j, "2": -1j, "3": -1 + 0j, "1": 1 + 0j}

points = [0j]

depth = 0

for _, _, color in moves:

dist, dir = int(color[:-1], 16), dirs[color[-1]]

cur = points[-1]

depth += dist - 1

points.append(cur + dir * dist)

And now to print the result, create a shapely Polygon from the points, buffer it properly, and ask shapely for its area:

poly = Polygon((p.real, p.imag) for p in points)

print("part 2:", poly.buffer(0.5, cap_style="square", join_style="mitre").area)

The tricky part here was figuring out how to buffer it properly. If you didn't buffer it, you'd be asking for the area of the shape enclosed from the center of each grid cell rather than the full area.

I tried to find a nice analytical solution for doing this, but I didn't succeed. I think I'll go read some other people's answers later to try and understand this better.

One advantage of having solved this with Shapely is that I can ask it for an SVG of the final shape:

Day 19

Day 20

For part 1, instead of my usual very-concise answers, I decided to create objects.

First, I set up some constants:

LOW = 0

HIGH = 1

DEBUG = False

Then, the Broadcaster:

class Broadcaster:

def __init__(self, targets):

self.targets = targets

def __call__(self, _, __, queue):

for t in self.targets:

queue.append(("broadcaster", t, LOW))

I gave each object type a __call__ method that accepted three arguments: the sender of the message, the voltage (HIGH or LOW), and the queue to put messages into. Each object then put the messages it wanted to send into the queue as a tuple of (sender, receiver, voltage).

The flipflop:

class FlippyFloppy:

OFF = 0

ON = 1

def __init__(self, targets, name):

self.state = FlippyFloppy.OFF

self.targets = targets

self.name = name

def __call__(self, _, pulse, queue):

if DEBUG:

print(f"{sender} -{pulse}-> {self.name}")

if pulse == HIGH:

return

if self.state == FlippyFloppy.OFF:

self.state = FlippyFloppy.ON

signal = HIGH

else:

self.state = FlippyFloppy.OFF

signal = LOW

for t in self.targets:

queue.append((self.name, t, signal))

And the conjunction:

class Conjunction:

def __init__(self, targets, name):

self.state = {}

self.targets = targets

self.name = name

def __call__(self, sender, pulse, queue):

if DEBUG:

print(f"{sender} -{pulse}-> {self.name}")

self.state[sender] = pulse

if all(v == HIGH for v in self.state.values()):

signal = LOW

else:

signal = HIGH

for t in self.targets:

queue.append((self.name, t, signal))

Read the input, parse it, and create our circuit:

items = {}

for line in sys.stdin:

item, targets = line.strip().split("->")

item, name = item[0], item[1:].strip()

targets = [t.strip() for t in targets.split(",")]

match item:

case "b":

items[name] = Broadcaster(targets)

case "%":

items[name] = FlippyFloppy(targets, name)

case "&":

items[name] = Conjunction(targets, name)

Set the state to LOW for all inputs of a conjunction:

# set the default state to low for all inputs of conjunctions

for name, item in items.items():

for target in item.targets:

if target in items and type(items[target]) == Conjunction:

items[target].state[name] = LOW

For part 1 answer, run the circuit 1000 times:

counts = {0: 0, 1: 0}

found = False

i = 0

for i in range(1000):

queue = []

counts[LOW] += 1 # button press

items["roadcaster"](None, None, queue)

while queue:

sender, target, signal = queue.pop(0)

counts[signal] += 1

if target not in items:

if DEBUG:

print(f"ignoring {sender} -{signal}-> {target}")

continue

items[target](sender, signal, queue)

print("part 1:", counts[LOW] * counts[HIGH])

This gives me my part 1 answer in .004 seconds, so I was hopeful for part 2 that I could just be dumb and run it to find the rx signal. Unfortunately, no luck on that front.

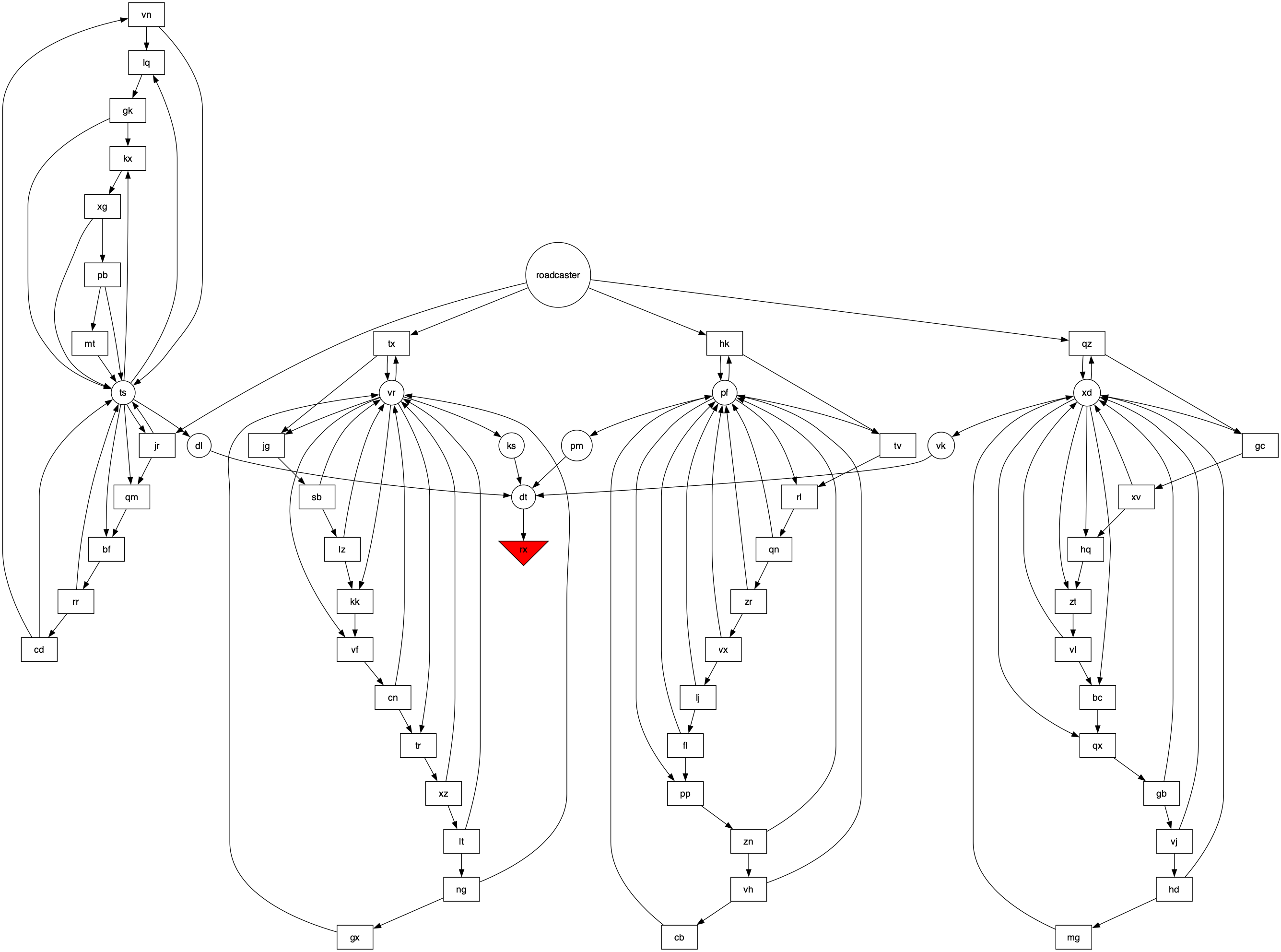

After letting it run for a couple hours while I did actual work, I figured I needed to find a smarter way, so the first thing I did was write some code to output a graphical version of the circuit using graphviz:

with open("g.dot", "w") as fout:

fout.write("digraph G {\n")

for name, item in items.items():

shape = "rectangle" if type(item) == FlippyFloppy else "circle"

fout.write(f" {name} [shape={shape}]\n")

fout.write(f" rx [shape=invtriangle style=filled fillcolor=red]\n")

fout.write("\n")

for name, item in items.items():

for t in item.targets:

fout.write(f" {name} -> {t}\n")

fout.write("}\n")

That code writes g.dot in the format that graphviz expects; then I used dot -Tsvg g.dot > graph.svg to render it to an SVG, which looked like this:

From here I could easily see that there were four circuits feeding into conjunction dt, which all needed to be HIGH for rx to receive a LOW voltage signal.

Then I wrote code to print out the run number each time one of dl, ks, pm, and vk sent a HIGH voltage signal, and found that all four of them had a simple cycle. dl fired every 3769 iterations, ks every 3917, pm every 3832, and vk every 3877. With memories of day 8 in my head, I crossed my fingers, called math.lcm(3769, 3917, 3832, 3877), and lo and behold I had part 2.